This has driven me mad many times over as reality has proven not to be as straightforward as marketed.

I want to shine some light on the often misunderstood sides of Scrum. The misunderstandings that usually lead to the infamous scrum-ish behavior, and to the subsequent chaotic working methods. I mainly want to write this to anyone in a situation similar to mine, who helped transform an organization from a project manager led “waterfall-like scrum” process to a more proper practice of Scrum. Hopefully you will also find tips on how to get the most out of Scrum in practice.

I’ve been a full-time Scrum Master for almost a year now, while getting excellent coaching from excellent people. Before that, I worked as a Vaadin Expert for roughly seven years, both using and developing Vaadin Framework. Of course I had heard of Scrum previously, but never really done it properly. I thought it was a good time to reflect back on my experiences and thoughts of Scrum.

Scrum Isn’t What Many Think It Is

I wish someone would have told me that the rituals and artifacts of Scrum are only a means to an end. I might even go so far as to calling Scrum a crutch that shouldn’t be leaned on too heavily for too long. Instead, Scrum is about the people practicing it. Problems don’t exist without people, and you fix problems by concentrating on each and every individual involved. None of the Scrum books braced me for this.

You’re not going to find answers to any particular problems you might have. That’s because I don’t know you, your people, your culture, or your project. All I’m trying to do is help people brace for the impact that is “proper Scrum”.

The Challenge of Culture

Vaadin is primarily a Finnish company with a primarily Finnish culture. We Finns don’t talk a lot, like to keep to ourselves and are inherently allergic to rhetorics. But it’s just culture, nothing more, nothing less. The important thing is that you can’t just turn a blind eye to that and pretend it’s not a factor. If you do, you ignore the people consisting of that culture – the ones that actually create things.

Scrum, on the other hand, has been developed in a culture where the opposite seems to be true - or so I can only assume. One of the key mechanics in Scrum are retrospectives; the activity where the team comes up with ways to improve their way of working. Keeping to yourself doesn’t work if you aim to fish for feedback. Also, it’s difficult to have a constructive conversation if you are uncomfortable with receiving feedback - us Finns aren’t the best at this either.

I’m sure there are other cultures out there where the assumptions and key mechanics of Scrum simply aren’t a match made in heaven. To make a key mechanic of Scrum work means sometimes either altering the culture in the people, or altering the processes that support those people.

At Vaadin, I think we are on our way to a good balance of changing the mindsets of our people, but also modifying the means and methods used in retrospectives. But this has taken time, conscious A/B testing and a good amount of effort. We’ve both coached the teams and toned down the aspects of retrospective activities that trigger the things perceived as *cough* BS and/or patronizing. It seems to work for us.

The Challenge of Arbitrarity

The Scrum roles, rituals and artifacts are all mere facades for something that a process-bound organization would understand. It’s not an ultimate truth that will save you from all bad things in life. Scrum, as it’s most often presented, is just a simplified formalization of a broad way of thinking, called agile and lean.

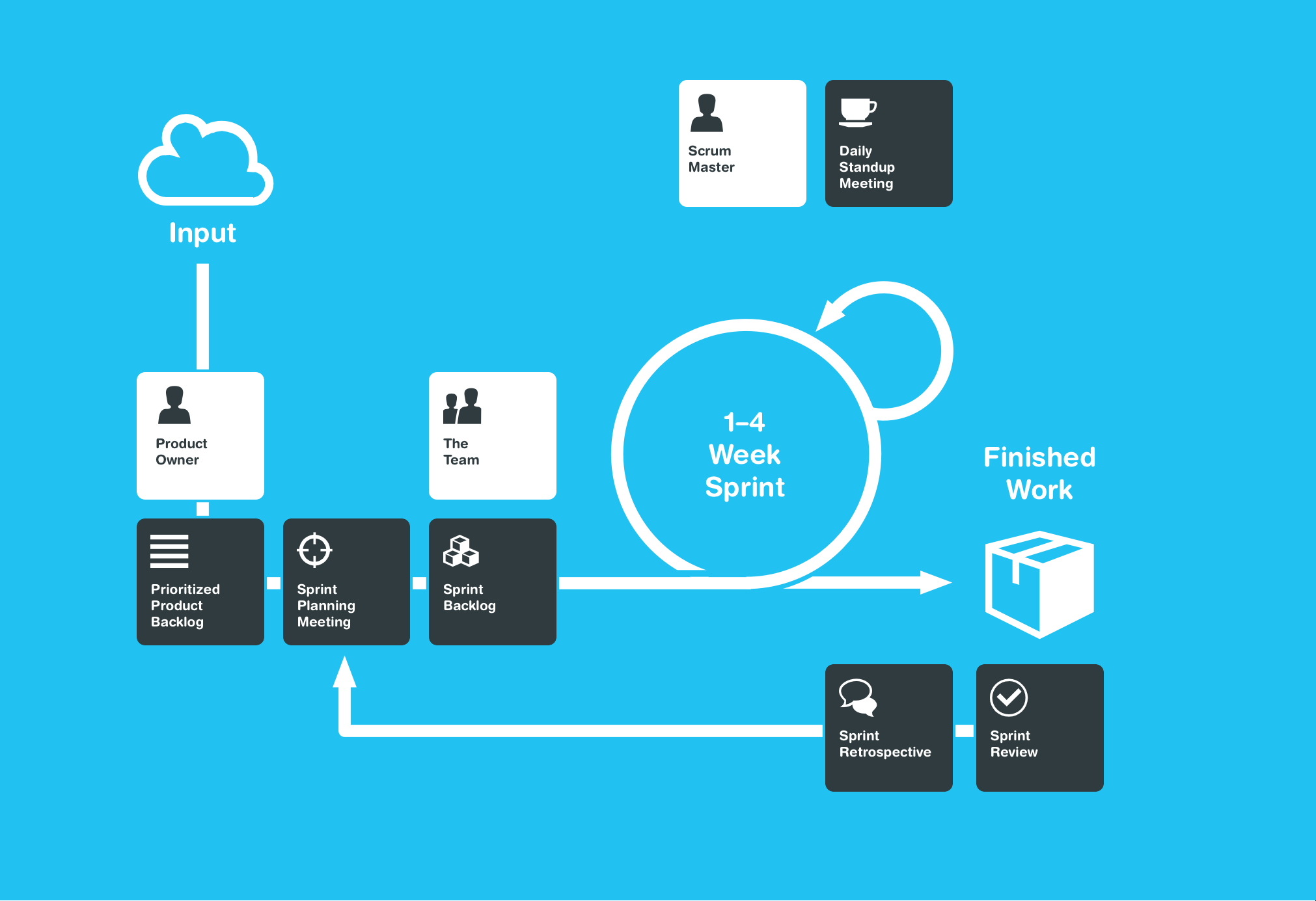

But, Scrum is a great communication tool! If you are dealing with an established organization with a lot of stiff red tape, Scrum is easier to talk about and more tangible than blatantly shouting “developers know best, it’s best to leave them be as much as possible” and expecting upper management to be properly excited about it. The benefits of the Scrum model come from the language it uses. It’s easy to recognize where all the named bits of Scrum fit into the “good ol’ waterfall” model. Looking from the opposite angle, it’s equally easy to see where the agile and lean ideas lie around the Scrum chart.

There are also a lot of things that many assume are an integral part of Scrum, but are never mentioned in the official Scrum texts. Velocity and task estimation are among them, worth dispelling explicitly. Scrum might or might not increase a team’s velocity. It depends on what it really stands for. The increase of velocity doesn’t necessarily mean that the team is doing things faster. Neither does the inverse hold true. A flat velocity graph can also mean just about anything. Estimation is such an immensely nuanced topic that I probably could write a whole new blog post just about that. Simply put, I’ve seen their pros and cons. And some pro for the team can be a con to the PO, or vice versa. Don’t assume that it’s strictly bad or strictly good as an exercise. Everyone needs to be acutely aware of these trade-offs, and adjust accordingly.

Once you get Scrum truly working, everyone in your company has greater insight into how things could improve further. The developers work smarter, and the stakeholders get what they find valuable sooner.

I haven’t seen any evidence for why it would be inherently supreme over something else that follows an agile or lean philosophy. It’s just one, quite famous, way to teach an established organization to become more agile in its movements, and lean in its practices.

The Challenge of Iterations

I firmly believe that some projects will suffer if they follow the Scrum model. Scrum is designed to isolate and funnel in small bits of chaos, one by one. We specify and lock as little chaos as possible at any one given time, and after a while we see what we got in our hands. If we have no idea what the future will look like, Scrum is awesome.

But that doesn’t work when everything needs to be known before we have even started. I would be very scared of crossing a suspension bridge while it is being built iteratively with e.g. Scrum. I would never put my head in an apparatus that shoots electromagnetic radiation through my brain, just because someone, in some room, yelled “hey guys, here’s an idea! Let’s see how far it gets us”.

It seems like too many people have chosen to turn a blind eye to the fact that Scrum is all about iterations. A sprint is meant to produce a completely functional product each and every time. The inevitability of that is that during the next sprint you will rip that product open and add stuff inside, and make sure that it’s shiny yet again. This causes ugly seams in the code. This is by design and by choice. Of course you’ll fix those later on, or risk decide to accumulate technical debt. The alternative to iterations is seeing the finished product at the end of everything, and getting something usable only after months or even years, rather than days or weeks.

Scrum slows the process down just enough to let people to stop and think about what we’re doing on a recurring basis. There’s no point in going full-speed in the woods if you missed the turn because you were too concerned on forward momentum rather than making the right decisions at the right times.

Think about how your projects have kept their deadlines and budgets, and whether or not they have delivered the specification that was decided up front. The million dollar problem, often literally, is knowing whether you actually are working in a static world, or a chaotic one.

The Challenge of Communication

We’ve had problems with lack of ownership here at Vaadin. For the majority of our history, our ways of working have been quite top-down: The Project Manager lists the features that need to be done, and then allocates people to work on those features as the PM sees fit. The coder codes, the manager manages. Any wrong moves will put the manager’s head on the line, so it’s her call. Not much discussion was going on there.

Now, all of a sudden, we have to teach people out of this bad habit. Instead, now we realize that each have their own domain of expertise. Both the coder and the product owner have their respective problem domains - one has a technical domain and the other has a business domain. This doesn’t work without excellent communication between the two parties. That means, being able to both express and understand communication across two very distinct problem domains.

A Scrum Master is first and foremost a facilitator. Someone who sits in the room. Someone who makes sure that the correct discussion is being held at the correct time, with the correct content, with the correct people, in a correct timespan. The job is to be silent and not impose opinions upon others. The books don’t tell you this. Or if they do, they don’t tell you how to do this. More importantly, they don’t tell you why to do this.

I can’t teach anyone how to communicate in the format of a blog post. But this is the “why”: You need to discuss about everything, in order to let the other party know what’s up, and be ready for the future. If communication doesn’t come naturally, the Scrum Master needs to know which discussions need to be held, and when. Forget status reports. Remember human interaction, in the hallway, preferably with a coffee mug in hand. Remember human judgement, as numbers can never tell the entire truth.

The Challenge of Education

To sum everything up, if you try to solve a problem with Scrum, you will have two problems: The first is the one that you already are trying to solve with Scrum. The other is that you now need to teach a lot of people to work and think in completely new ways. Scrum is not something that you can smear on top of your current working practices, like you’d smear some icing on a cake.

You need to stop doing any stupid things that you’re currently doing, and instead do things that are smarter than before. This makes many people very upset. The philosophy here is that some people hate feeling stupid. Doing things that you don’t know how to do is hard, and that makes some people feel stupid. Thus, some people hate doing things in a completely new way.

An agile conversion is a full-time teaching job. Shouting orders and forcing people into a mold is not teaching. It’s shouting, blaming and guilting. Making people understand the reasons behind actions, and having them intrinsically want to do things the right way calls for a huge amount of pedagogical skills from the agile coach. Psychology, empathy, sympathy, communication, patience... All those soft skills that are depressingly rare in-house in many tech companies.

You need both good teachers and good students for Scrum to succeed.

People Solve Your Problems!

If you have only one take away from this text, let it be this: Problems are solved by people and communication, not processes.

Scrum is merely a means to an end. The Scrum framework helps by guiding you in how to communicate. Adding a Scrum Master into a team is just the first step, the true goal is to make the Scrum Master obsolete.